Tuesday, June 29, 2010

You want me here for sex, don't you?

One of my friends has gone wild filling out Flixter Top 5 lists on Facebook and one in particular caught my eye: Top 5 George Romero. The omission of a particular movie made me gasp with indignation, especially since my friend (yeah, you Freddy!) is supposed to be a huge Romero fan. I pointed out this injustice (or what I concluded had to be a lapse in judgment due to the fact that he gets too much oxygen up there in Eugene, Oregon) and he replied that he had not seen it. Whuuuut???

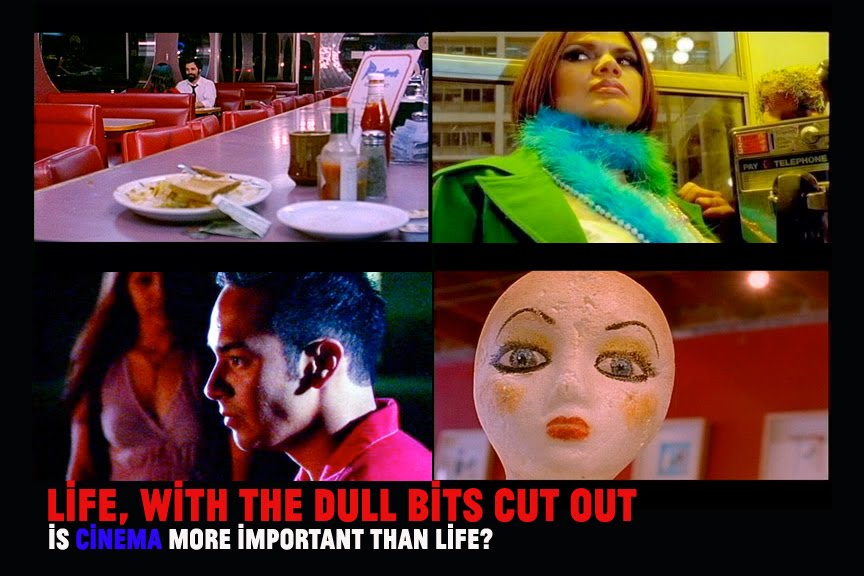

Those who call themselves horror fans (Freddy) already know Martin well (not Freddy). After his initial 1968 success with Night of the Living Dead, Romero had three box-office failures, resulting in his switching to making documentaries for four years. In 1977 Romero returned to feature film making with Martin, a study of a troubled youth who may or may not also happen to be a vampire. Over the past 30 years Romero's vampire work and his personal favorite, has attracted a strong following of admirers. It’s undeniable that this 1970s reworking of vampire mythology is a multi-layered achievement which demands serious consideration. Martin was for some time Romero’s most talked about but least seen film, the perfect conditions for the birth of a cult, and one whose steady growth has been matched by an increased critical appreciation of the horror film as a vehicle for social commentary.

Vampires have been really “in” for quite some time. The development of the genre has seen the figure of the vampire shift steadily in locale and class, moving closer to home and descending in rank as the years have passed. It has given us a lot of classics (Nosferatu, Vampyr), but it wasn’t until Martin that everything changed. (Let the Right One In is not as original people might think.) Very much a film of its changing times, Martin was the first vampire movie to completely shake off the genre's folklore origins and the shadow of novel that effectively shaped the first 50 years of vampire cinema. It recognized the shifting nature of both the horror audience and the fears of the society in which they live, a post-Charles Manson era in which you could be killed for no even remotely logical reason by the guy who lives just down the road. This is recognized even in the film's title. Like Dracula, the most famous vampire tale of them all, the name of the vampire is the name of the film, but whereas “Dracula” invokes a sense of the exotic, the mysterious, the foreign, Martin is deliberately ordinary, an everyday name that has no specific connotations other than its day-to-day familiarity.

Martin brought the vampire onto our doorstep and stripped him of nobility – he is an ordinary kid and he lives in a spare room in his cousin's house. He has no bride, no girlfriend, and unlike the sexually potent vampire of films past, is actually afraid of women and sex. Martin is the boy next door, the reclusive, uncommunicative kid, the loner that Homeland Security would peg as having terrorist potential. He's the shy boy who one day shocks the neighborhood by doing something horrible and out of character that, just for a few moments, makes him special. Most of all, he is the product of his family and environment – all his life he has been told he is bad and now he believes it and acts accordingly.

Romero sets his story in a decaying Pittsburgh suburb populated by aging, superstitious immigrants. Romero's pseudo-vampire is Martin (John Amplas), an awkward teenager with few social skills and a sadistic habit of feeding off the blood of innocent victims he methodically drugs and rapes. But despite his thirst for blood, Martin doesn't have vampire's teeth; he's immune to crucifixes, garlic and priests. So what exactly is he? Fortunately, Romero never answers this question and opts instead to define Martin as a product of his environment, a town populated with ugly, superstitious, immoral, criminal and suicidal depressed individuals. As evidenced in a number of scenes, if Martin doesn't kill you, life will.

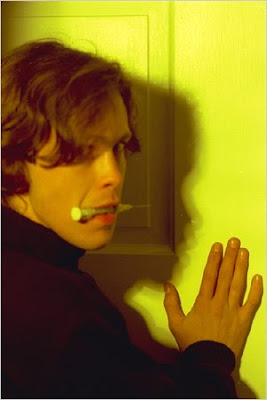

In perhaps the most iconic image in modern vampire cinema, Martin is briefly framed at his victim's door with a syringe held ready in his mouth (the image will recur later). The needle replaces the fang – both are used to sedate and ultimately destroy the vampire's prey, but while the traditional elongated canine teeth link the vampire to the wolf into which he is fabled to transform, the syringe has, for most, very unpleasant real world associations. It's clinical, surgical nature directly reflects Martin's approach to his assaults, which are executed like military stealth operations. Brilliantly constructed and edited (the use of rapidly cut huge close-ups is particularly impressive), this is a nonetheless deliberately confrontational and uncomfortable opening. How could any audience sympathize with such a central character? Enter Tada Cuda. But I will stop right here, for fear I might spoil it for those who have not seen the movie (Freddy!).

Even though the quality of Martin is hampered by its budgetary restraints, these flaws help Martin transcend the typical constraints of the vampire genre. As a result, Martin is afforded the ability to be disturbing in ways that emulate the horrors of raw, real-world footage. Martin concludes with an abrupt, brutal and final act, an act that puts to death the significance of whether Martin was or wasn't a vampire. In the end, all that matters is how cold and unforgiving the world is and how it leaves us with few choices. The ultimate choice and perhaps the worst one of all: Kill or be killed.

Ironic as it may be, it’s also typical of great true independent cinema that one of the most intelligent and revisionist of modern vampire movies may not be a vampire movie at all. It's a question that has hovered over the film ever since its release and is central to its narrative – is Martin Madahas an 84-year-old vampire or a mixed-up kid with psychotic tendencies? This may be the primary question asked throughout Martin, but it isn't the most important one. The question worth asking is: nature or nurture? Romero's script is one of his best, a (literally) biting commentary on a post-Watergate, post-Vietnam, blue-collar America: disillusioned, depressed and depraved. Either way, Martin is a genuinely great vampire movie, one that recognizes and fully understands generic conventions and yet turns most of them completely on their head.

Martin takes the codes and conventions of the vampire genre and reworks them to remarkable ends, with one eye on the past but the other fixed firmly on the society in which the film was made. In that respect it has to be seen as the first truly modern vampire film, a strikingly intelligent, inventive and socially relevant take on a genre that even in the 70s was still hanging onto the coat-tails of the Transylvanian Count whose story gave it birth. Martin contemporized the vampire tale, not by transporting Dracula to swinging London in 1972, but by exploring modern fears through modern eyes and confronting the audience, perhaps for the first time, with what it really means to be a vampire. That it remains so fresh a work today is, ironically, in part due to its lack of mainstream success. When commercial cinema eventually re-embraced the vampire film in the 1980s, it had learned little from Romero's extraordinary work, the younger protagonists of The Lost Boys – dressed to look cool and pining for MTV – having more to do with audience demographic than a desire to explore the genuine fears of society or the traumas of youth. In this respect Martin is even today a unique work, a low budget gem of extraordinary depth and complexity that showcases Romero on phenomenal form both as storyteller and filmmaker, and built around an utterly convincing central performance by the young John Amplas and a support cast of largely natural nonprofessionals. There is simply no contest here – Martin is THE modern vampire film. End of story.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment